The Importance of Ending on a High Note

Over the past 20 years, behavioural economists have found evidence in support of a human insight that story-tellers have known for countless generations – people love a happy ending. However, the particularly curious part of this insights is that all else being equal, an experience that starts off as happy/positive is not remembered as favourably as an experience that ends off as happy/positive. That is, it is not just the case that people love happy endings, but that they love them much more than happy beginnings.

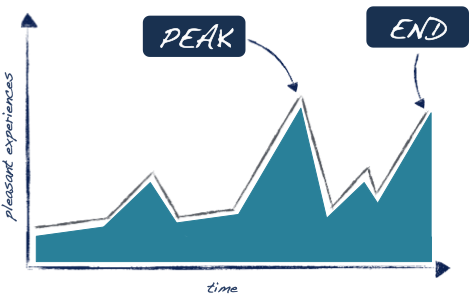

The behavioural economist, Daniel Kahneman, labelled this heuristic the Peak End Rule, and attributed it to situations where people are susceptible to misremember experiences that ended off on a positive note. In those situations, people are more likely to overemphasize the peak of an experience and the end of the experience in their memory. As a result, when they remember that particular experience their memory of it is biased by the peak and end point, and they are less likely to remember the rest of the experience. Essentially, how we remember an experience is not a reflection of the sum of all the parts of an experience, but it is a reflection of the high point and ending point.

The Peak End Rule

Even though the Peak End Rule may seem like common sense, there is a critical nuance to it that I want to make sure you do not overlook. The key to the Peak-End Rule heuristic that I want to focus on is how it biases how we remember positive and negative experiences, regardless of how we actually felt about the experience in-the-moment. Kahneman referred to this distinction as our “remembering selves” and our “experiencing selves”. In-the-moment, our “experiencing selves” would prefer to put off negative/unenjoyable experiences until the end. Think of all the times you put off doing housework on the weekend, waited to file your taxes, or delayed your trip to the gym, all in favour of a more immediate positive experience. You may rationalize the decision to yourself by saying ‘What is the difference if I do something I enjoy now and something I don’t enjoy later versus doing the opposite? If the overall experience is made up of equal parts “enjoyable” and “unenjoyable”, then what does it matter what order you experience them in?’ Well, it turns out that the order matters a lot because how the experience ends has an overwhelming influence on how it will be remembered.

The Strength of an Irrational Bias

Daniel Kahneman and colleagues illustrated how the Peak-End Rule can irrationally alter how we remember an experience in two very distinct, but quite unpleasant scenarios. In the first study, Kahneman and colleagues placed participants in one of two different versions of an unpleasant experience – they had to keep their hands submerged in cold water. In the first version of the cold-water test, a group of participants kept their hands submerged for 1 minute before taking them out of the water. In the second version of the cold-water test, the same group of participants kept their hands submerged for a minute in the same water temperature as before, but after the minute was up they had to keep their hands submerged for another 30 seconds in water that was only slightly less cold.

After both versions were completed, the participants were given the choice to pick which of the two options they’d prefer to repeat. Surprisingly, the participants preferred to subject themselves to the second version of the cold-water test despite the fact that the second version exposed them to unpleasant cold-water conditions for an even longer time. Kahneman concluded that people preferred the longer, more unpleasant version of the cold-water test because the relatively “less unpleasant” end to the experience biased people to misremember the experience under a more positive light.

Disregarding Unpleasant "In-the-Moment" Experiences

Kahneman and colleagues ramped the unpleasant experience scenario up in the second study to demonstrate how the Peak-End Rule can bias our memories under “real life” circumstances. In this study, the researchers examined the feedback from patients that underwent an unpleasant medical procedure – colonoscopy or lithotripsy (i.e. removing kidney stones) – and compared the patient’s feedback with the patient’s real-time measure of discomfort. They found that patient’s feedback (or their memory of the experience) was largely determined by the level of discomfort at the most extreme point and towards the end of the medical procedure. Patients that experienced a higher level of discomfort at the end of the procedure were found to misremember the experience as being more negative than it actually was in-the-moment.

Remember, the researchers have recordings of the patient’s discomfort level during the entire procedure, so they can go back and see how long a patient was exposed to discomfort during the procedure, and/or how intense the discomfort felt from moment to the next. But all that mattered for the patient was how they remembered feeling at the end of the procedure, regardless of whether they had a long, uncomfortable procedure or initial periods of extreme discomfort. Just like in the cold-water test, the Peak-End Rule explained why people seemed to irrationally discount the sum of their unpleasant experience, and only focus their memory on how the experience ended.

Applying the Peak-End Rule to Improving the Customer Experience

Even though those studies used some odd scenarios to make their point, they still illustrated how introducing an enjoyable peak at the end of an experience can overcome a more difficult/negative moment initial experience. If the Peak-End Rule can be applied to colonoscopies and some form of weird cold-water torture, then certainly it can be applied to improving a customer experience. The straightforward applications of the Peak-End Rule are to introduce positive moments at the end of any customer service complaint/issue (e.g. ensure that negative customer experience is always followed by a positive interaction), but the real value of the Peak-End Rule is building it into the overall customer experience.

Where are the Online Peaks?

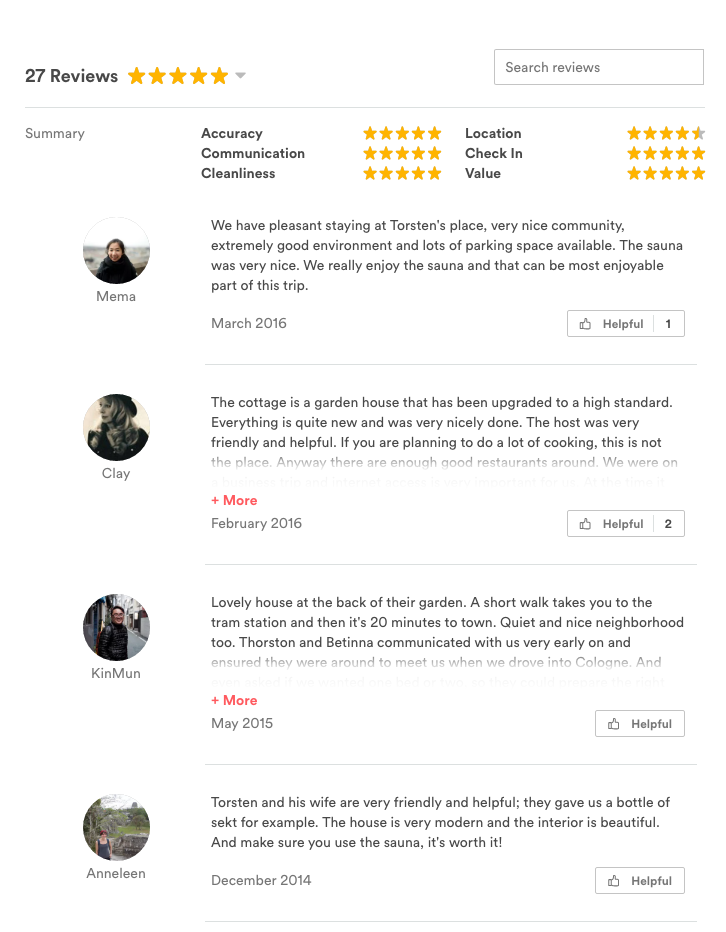

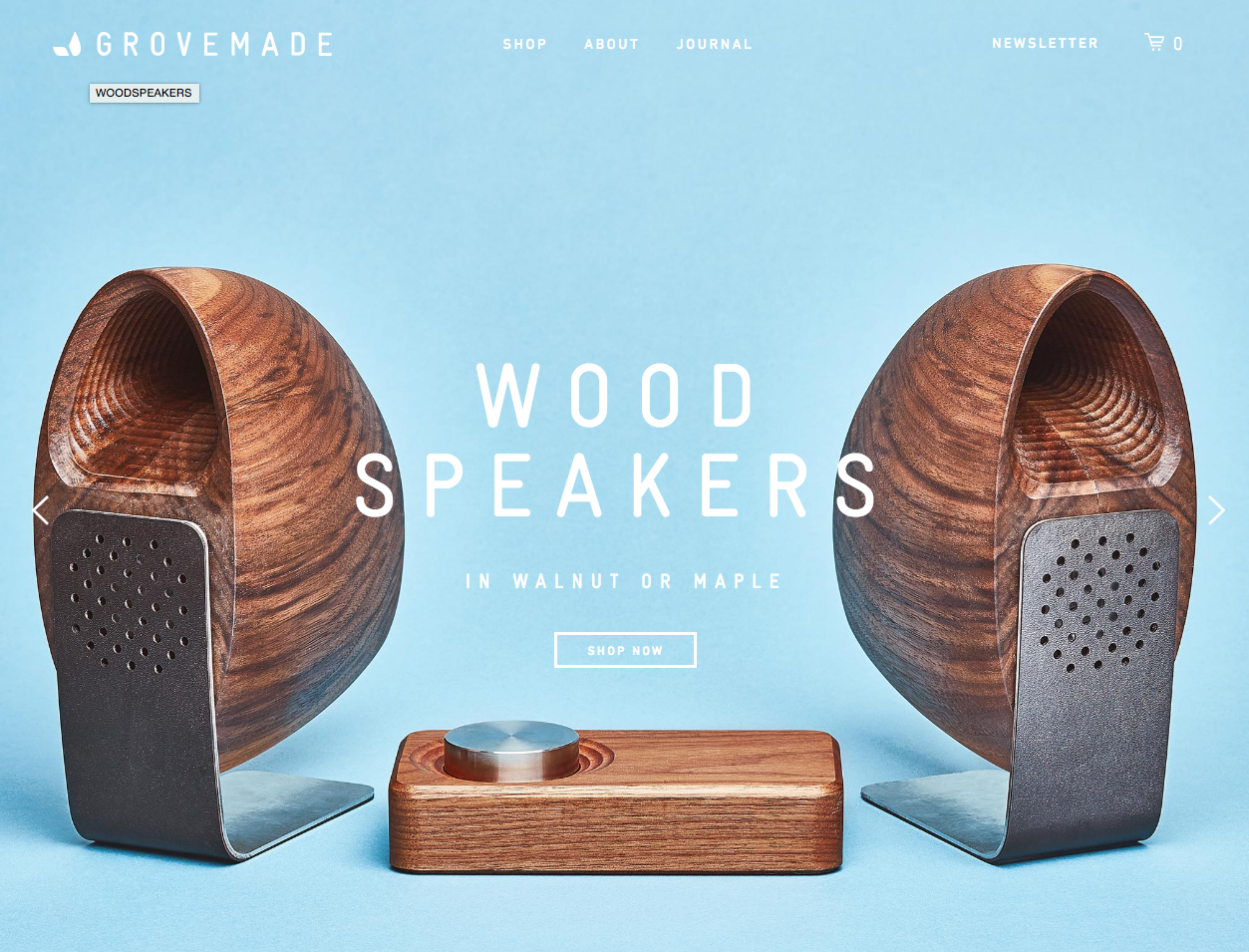

The Peak-End Rule has the best applicability to online shopping where the user experience is constantly evolving. In particular, the focus for e-retailers is on creating enjoyable experiences in the early stages of their shopping experience, when customers are “window shopping”. Think about all the user experience improvements that e-retailers have adopted in an endless attempt to keep potential customers engaged - infinite scrolling (however, see this article on why infinite scrolling failed for Etsy), recommendation engines; visually striking images; customer reviews; even augmented reality. Yet, very little attention is ever paid to improving the user experience in the last customer touchpoint. This is particularly concerning for e-retailers since they can create the best shopping experience imaginable on their site, but if a customer encounters a problem during the checkout stage, then all those positive experiences are negated.

Importantly, it is not difficult to create positive experiences in the last customer touchpoint. Even simple pleasantries can be incorporated into messaging in the last touchpoint an e-retailer has with their customer. As for the disgruntled customers, e-retailers can quickly follow up with them via e-mail or social media messaging with a positive message (e.g. a promotion, a personalized response) to ensure that at the very least, the last experience that customer will remember will be a positive one.

But, where I think the Peak-End Rule has the greatest applications for e-retailers is to rethink the user experience at the checkout stage. Too often, e-retailers seem to resigned to the fact that the checkout stage of the customer journey is going to be a pain-in-the-ass. Customers need to provide billing information, shipping information, personal information, all of which becomes increasingly more complicated for new customers; yet, very few e-retailers have tried to create unique, positive experience during those final steps. The main reason why e-retailers have not perfected the final steps of their customer journey is because it is a lot easier (or more fun) to make an engaging experience while customers are "window-shopping", rather than filling out forms. But, even if e-retailers are struggling to create positive peaks at the end of their customer journey, then the next best thing would be to make the unpleasant checkout experience as quick and painless as possible (e.g. Amazon's "Buy Now with One Click" Button).

Amazon's workaround for the Peak-End problem - the Buy Now with 1-Click button - making the End as quick and painless as possible.

It is important to keep in mind that the Peak-End Rule does not require that the last customer touchpoint be the best experience, it just has to be relatively better than the most unpleasant experience. Just like in the cold-water test and the colonoscopy example, the last part of those experiences weren't particularly pleasant, they were just relatively less unpleasant. E-retailers do not need to reinvent the wheel to take advantage of the Peak-End Rule, they just need to find a way to make the last experience a little more pleasant than filling out your credit card information. If it worked for a colonoscopy procedure, then e-retailers should have no excuse.

Want to share your thoughts? Feel free to share them in the comments section below or on social media.

Explore the challenges and promise of Nudge Theory in climate action with our latest article, 'From Page to Practice: The Power and Pitfalls of Applying Nudge Theory for Climate Action.' We delve into how the simplification of choice architecture and neglect of larger systemic influences can impact the effectiveness of nudges. However, by acknowledging these criticisms and strategically directing nudges at the systemic level, we can potentially drive large-scale transformations in our fight against climate change.